Who Has the Right to Tell Polynesian Stories? Animator Buck Woodall Sues Disney Over Moana:

In a high-profile lawsuit filed in a California federal court, animator Buck Woodall has accused Disney of stealing his ideas for their Moana franchise. Seeking $10 billion in damages, Woodall claims that the Moana storyline and visuals were lifted from his animated project Bucky, a story set in an ancient Polynesian village that he says he worked on for 17 years.

The case has sparked debates not only about intellectual property but also about cultural storytelling and the responsibilities of creators working with Indigenous narratives.

The Lawsuit: Woodall vs. Disney

According to the lawsuit, Woodall alleges that Disney’s Moana—including its forthcoming sequel—borrowed heavily from his copyrighted screenplay and trailer for Bucky, originally registered in 2004 and updated in 2014. The plot of Bucky, as described by Woodall, follows teenagers in a Polynesian village who embark on a quest to protect their homeland, a premise he believes strongly resembles Moana.

The complaint further alleges that Woodall’s former colleague, Michael Marchick, shared his materials with Disney, leading to their alleged appropriation. His lawsuit states:

“Disney’s Moana was produced in the wake of Woodall’s delivery to the Defendants of virtually all constituent parts necessary for its development and production after more than a decade of effort.”

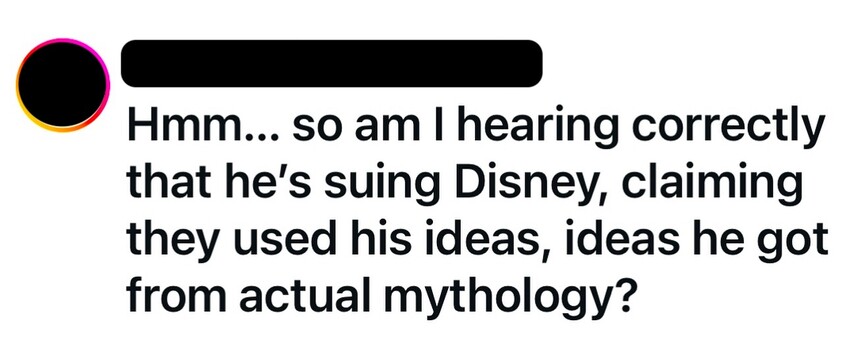

While these claims will be tested in court, the case raises broader questions about cultural ownership. Woodall’s assertion that he owns the rights to a Polynesian story is particularly controversial given that Polynesian culture is rooted in communal narratives passed down through generations.

Disney and Cultural Representation

Disney’s Moana has been praised for its commitment to cultural consultation, involving a group of Pacific Islander cultural advisors known as the Oceanic Story Trust. This group worked closely with Disney to ensure the film honoured Polynesian traditions, myths, and values. From Māui, the demigod inspired by Polynesian mythology, to the design of the voyaging canoes, Moana was lauded for elevating Polynesian voices and celebrating their heritage on a global stage.

However, some critics argue that Disney’s efforts, while commendable, do not completely absolve the company of perpetuating a long history of commodifying Indigenous cultures for profit. As noted by Mārata Ketekiri Tamaira, Moana can be viewed as both “a product of Disney” and “a strategic site for Indigenous participants to exercise stewardship over their respective cultures”.

The sequel, Moana 2, further increased Polynesian representation, with Dana Ledoux Miller and David G. Derrick Jr.—both of Polynesian heritage—directing the film. Additionally, many Polynesian actors, including Auli’i Cravalho (Moana), Temuera Morrison (Chief Tui), Rachel House (Gramma Tala), and Jemaine Clement (Tamatoa), brought authenticity to the project.

Disney remains a multinational corporation, and while it consulted with Polynesian experts, the creative and financial control ultimately rested with non-Polynesians. The question lingers: does this level of collaboration adequately compensate for centuries of cultural appropriation by Western entities?

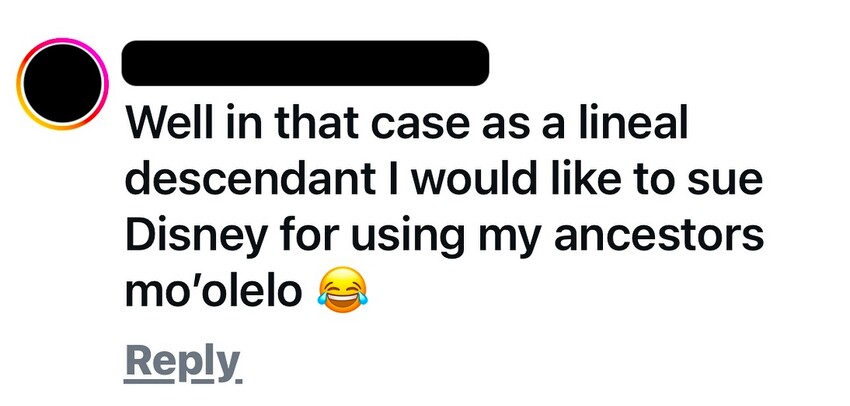

The Irony of Woodall’s Claim

Woodall’s lawsuit adds a layer of complexity to this debate. While he accuses Disney of copying his work, his claim to ownership over Polynesian-inspired narratives is itself contentious. Woodall’s Bucky project, by his own admission, was a product of his interpretation of Polynesian culture. His legal argument hinges on whether he has a right to assert ownership over stories derived from traditions that do not belong to him.

It is also important to note that Woodall was born in the Pacific Island of Hawai‘i. However, he has never claimed any Polynesian heritage, nor has he mentioned any Polynesian persons involved in the making of Bucky. This context adds another layer of complexity to his claim of ownership over a story rooted in Polynesian culture.

Is Collaboration Enough?

Disney’s efforts to include Polynesian voices in Moana represent a step forward in how Indigenous stories are told in mainstream media. As Samoan filmmaker and Oceanic Story Trust member Dionne Fonoti noted, “Moana may not be perfect—what film is?—but it cannot be denied that it was made with a deep sense of responsibility, thought, and care”.

Even with these measures, the film’s creation and distribution were ultimately controlled by Disney, which reaps the majority of the profits. This dynamic underscores the ongoing imbalance in power and representation. While consultation is an improvement over outright appropriation, critics argue that true equity would involve Polynesian creators leading such projects and retaining creative and financial control.

The Larger Conversation

The Woodall vs. Disney lawsuit is about more than intellectual property—it’s a microcosm of a larger conversation about cultural storytelling in a globalised world. Both parties face scrutiny: Woodall for his claim to ownership over a culture not his own, and Disney for its role as a corporate entity profiting from Indigenous narratives.

For Polynesians, this case highlights the importance of protecting their stories and traditions from being commodified without meaningful involvement or benefit to their communities. While Disney’s collaboration with cultural advisors and local talent is a step in the right direction, it also raises the question: Is it enough for global corporations to consult with Indigenous voices, or should these voices lead the storytelling process and financial gain?

As the lawsuit progresses, it will not only test the boundaries of copyright law but also challenge society’s understanding of cultural ownership in an era where Indigenous stories are increasingly sought after—and monetised—by outsiders.

-

By Tikilounge Productions & Creative New Zealand Toi Aotearoa

Arts & Culture Journalist Destiny Momoiseā