ʻO le Tala o le Māfua'aga o le Tuiga' - The Origin Story of the Tuiga

By Jake Fitisemanu Jnr.

There was once a taupou named Vītaliutaolepaepae(1), the daughter of orator chief ‘Ulu(2) who lived in Puipa‘a village, Faleata district, ‘Upolu island. Vī was renowned throughout the islands for her beauty -- especially her wavy, brown hair -- of which she was extremely proud and boastful. Her pretty friends (also the daughters of chiefs) were just as conceited and self-centered, and they relentlessly teased all the other girls in the village.

After years of hearing the villagers complain about his daughterʻs bullying, chief ʻUlu had had enough of her childish ways. He told Vī that it was time to grow up, and that she had one year(3) to choose a husband to settle down with. Vī hoped that if she made the selection criteria stringent enough, that no man would be eligible, and she could stay single and carefree forever(4). “In order,” she said, “to ask for my hand, he must be the handsomest in all the land.” She also insisted that her groom be a tautai folau (navigator, master seaman) so that she could sail and travel at her leisure(5). Besides being good looking and knowing how to sail, the suitors were instructed to guess Vīʻs favorite fish -- out of all the fish species in the sea -- and present her with a fresh catch.

Handsome young men began arriving in front of ʻUluʻs house every morning, hauling their canoes ashore with baskets full of fish in the hopes of correctly guessing Vīʻs favorite. The handsome king of ʻUvea brought her a fierce mago (shark)(6), a warrior from Fiji caught her a whole school of tuna (asi), a prince from Tonga even brought her a huge whale (tafolā), but no one succeeded in catching her favorite.

Several months into the courting competition, an old, weathered navigator from Manu‘a named Lele anchored at Puipaʻa and sat at the edge of the malae watching the endless line of hopeful suitors present their fish to Vī, only to be rejected and sent home. Lele was the official tautai of the powerful Tui Manu‘a (King of Manuʻa) and while he was not good looking, he was very clever. He approached one of Vīʻs servant girls with an offer, “Pepe,” he said, “if youʻll tell me the right fish, I promise to give you whatever you wish.” The servant whispered to Lele, “ok, Iʻll make this deal with you… the fish you need to catch is the orange tuʻuʻu.(7) Pepe the servant told Lele that her wish was to be freed from her dreary life of waiting hand and foot on Vī, who was beautiful on the outside, but a horrible person on the inside.

Lele launched his canoe and returned with a handful of tu‘u‘u (clownfish). Lele was a navigator and he had the right fish, but he needed to find a way to meet the “handsomest in all the land” criteria in order for Vī to choose him. In fact, Lele was far from handsome -- his head was bald, with sunken eyes, his stomach wobbled when he walked, and his skin was tough and leathery. Thinking quickly, he husked a coconut and covered his baldness with a wig made from the brown husk fibers; he used sticks and seashells to make a flashy headdress with tall ornaments high above his head that took attention away from his unpleasant face and sunken eyes; then he smeared himself in coconut oil to tone his leathery skin. Satisfied with his disguise, he threw a pair of tu‘u‘u into a basket and headed back to the village. Waiting until nightfall (to further mask his appearance), Lele called at Vīʼs house and presented the basket of tuʻuʻu as he asked for her hand in marriage. His disguise worked! Vī was impressed by Leleʻs stories of all the exotic lands he had sailed to, and since he obviously knew her well enough to guess her taste in fish, his proposal was accepted.

As the village bustled in preparation for Vīʼs wedding, Lele sought out Pepe (the servant who had revealed Vīʼs secret) and thanked her for her assistance. Both smiled as their plot had made them both happy, Lele had a beautiful bride and Pepe was freed from servitude. Their joy was short-lived, however, as someone had overheard their conversation and reported the deception to Vī and her father. As punishment, Vī ordered the servant to marry Lele instead and return with him to Manuʻa at first light. Before she left, the angry maiden took her revenge by waiting until Vī fell asleep and cutting off her long, beautiful, brown hair(8).

On the voyage to Manuʻa, the handmaid discovered that Lele wasnʻt very handsome without his disguise on, but that he was kind, respectful, and wise. Lele found that his new wife was not as beautiful as Vī, but unlike the arrogant taupou, Pepe was caring, witty, and attentive(9). Arriving at Taʻū, Lele told the king of his adventure and how he succeeded in winning (and losing) the hand of the famous taupou, Vītaliutaolepaepae.

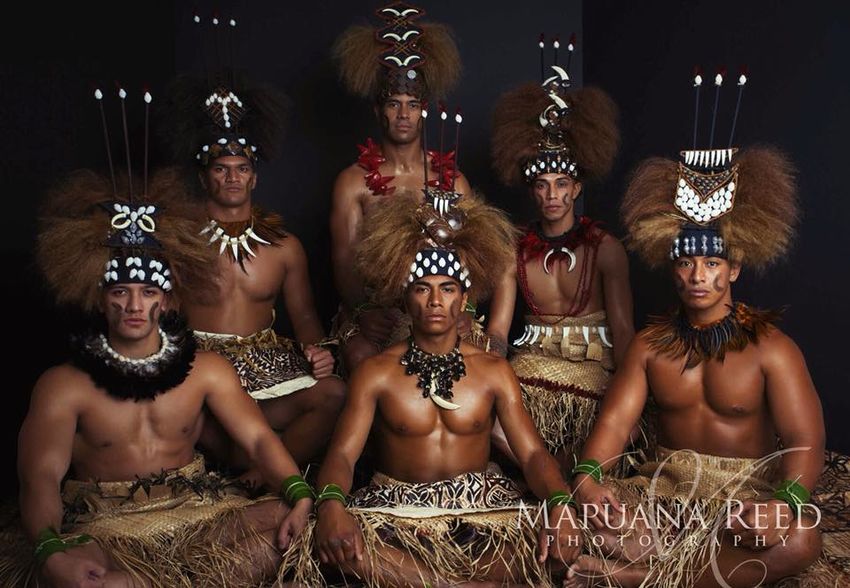

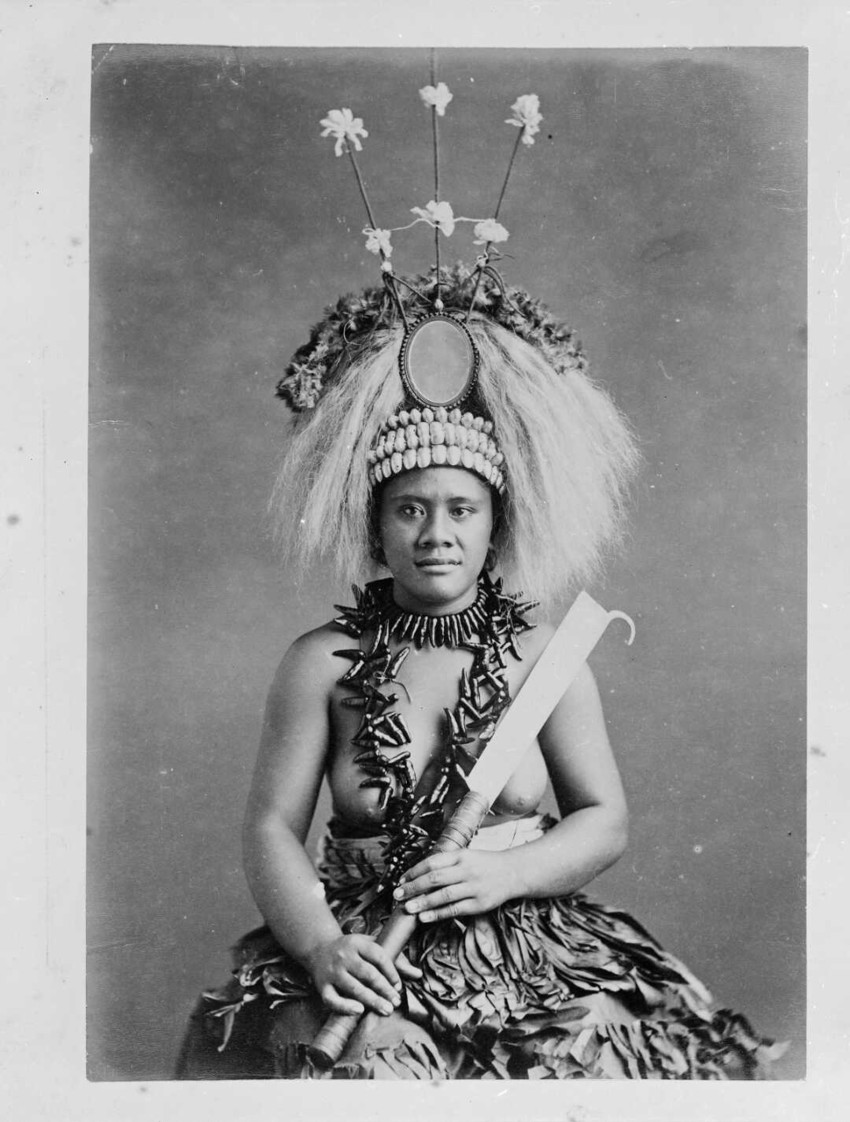

The Tui Manu‘a asked Lele to show him the disguise he had made and was quite amused that the shabby costume was able to fetch him a wife. Tui Manu‘a called the disguise a “tuiga” because it was “pieced together” (tui)(10). The aging king wondered if this headdress would improve his own appearance, so he asked Lele to make another. But rather than the makeshift costume he hastily threw together in the bushes, Lele used the finest materials at his disposal -- turtle shell (una), gold-lipped oyster shells (tifa)(11),and pearly nautilus (fuiono). Pepe replaced the coconut husk wig with locks of Vī’s beautiful hair, added a carved comb (selu tuiga), and long red tava‘e feathers(12). The Tui Manu‘a was so pleased with the tuiga that he decreed that despite its humble origins, the tuiga would forever be reserved for the sons and daughters of royalty and nobility.

Beside the various morals of the story (such as the “golden rule,” donʻt be a bully, donʻt judge a book by its cover, and donʻt be afraid to try new/hard things), there are also several cool linguistic dynamics embedded in this story. The crownland of chief ʻUlu in Puipaʻa village, where the majority of this story allegedly took place, is still called Vaialasa -- “waters of desire” -- supposedly because ʻUluʻs front yard became a giant puddle of water from all of the eager suitors arriving wet from the sea, carrying soaking baskets of fish, and washing the salt water off of their bodies before presenting themselves to Vītaliutaolepaepae. When the tuiga is worn in public it is known as fa’alelega or “flying the tuiga,” because it was first worn by Lele (“lele” means “to fly”). When a tuiga is worn for a performance or ceremony, the head motions of the wearer are called “taupepepepe” or “fa’apepepepe,” because the finishing touches of the first tuiga were added by Pepe (“pepe” refers to the graceful fluttering of butterfly wings).

In old Sāmoa, the tuiga was always considered ‘oloa or “men’s products,” since Lele was the first craftsman. Only recently did tuiga-making become a women’s practice as western, colonial opinion deemed items like feathers, locks of hair, seashells, and headbands to be “feminine.” Modern tuiga are typically made as a single-piece “hat,” while traditional tuiga are comprised of four components: the nautilus shell headband (pale-fuiono)(13), the vertical framework (lave), the sega feather ornament (ʻie ʻula), and strands of human hair (lauao)(14). The hair of deceased ancestors was collected, washed, and bleached and added in successive layers, so that when someone wears a tuiga, they literally and symbolically embody the mana and identity of their ancestors.

Cover Image: Tauivi Designs Photo Credit: Mapuana Reed

.

References:

* Her saʻotamaʻitaʻi title was Alofasaupō. Her personal name is apparently a descriptive nickname (or posthumous name), taken from the phrase ʻo le vī na tali uta i le paepae (“the ambarella fruit left waiting on the house platform”), referring to the custom of villagers who encountered ripe vī and would leave them on the steps of the faletalimālō for any children or passersby to enjoy. At the end of the day, the fruit still remaining unselected were those that were bruised, rotten, or worm-eaten. A poetic allusion to the “picky” nature of the taupou, as well as foreshadowing of the taupouʼs lifelong “unselected” status.

2. Because ʻUlu was a prestigious figure in the Faleata subdistrict, his title was subject to the traditional Samoan igoasā/tapuigoa custom of verbal avoidance. Hence, in Faleata the breadfruit is called faʻatau rather than ʻulu, in order to avoid saying the elevated chiefʼs name in vain. This practice still exists among older Faleata people today, but is not as strictly enforced as it would have been in former times. Other examples of tapuigoa include the substitution of aua for ʻanae in Falelātai (where ʻAnae is a chief title), the former use of manu in place of moa in Manuʻa (in respect for the Tui Manuʻa/Moa family), fuāuli for talo in Sātalo and Falealili (where Talo is a prominent chiefly name), etc.

3. The word used in the Samoan telling is tausaga, which, prior to the introduction of the Gregorian calendar, actually referred to a six-month season, rather than a 12-month year. The two tausaga of the traditional Samoan lunar calendar were the Vāitoʻelau “dry season” (literally, “duration of the northerly winds”) from roughly April to September, and the Vāipālolo “wet season” (literally, “interval of the coral spawning”) from October to May.

4. Prior to the imposition of Victorian, Christian constructs of matrimony, Samoan women (in general) had considerably more power and discretion over their marital situations and domestic dynamics than Christian “matrimony” would allow. Pre-colonial social institutions acknowledged that women produced everything of material value in Samoan society -- utilitarian necessities (floor mats, clothing, figota, etc.), tōga commodities (fine mats, siapo cloth, etc.), not to mention they birthed and raised the suli heirs of Sāmoaʼs high families. This elevated social status gave women prerogative within marriages (typically arranged unions in serial monogamy), with the success and longevity of the relationship incumbent on the husband and his family. A highborn Samoan woman had full entitlement to leave an arrangement if she was dissatisfied for any reason, and when she left, she had rights to take her dowry and her children with her. Custom dictated that a “returned” wife was presented to her family laden with “apology gifts” that typically exceeded the value of her original dowry. Not only was it a massive expense, it was an extraordinary blow to the prestige and reputation of the husband and his family, so it behooved a husband to do everything humanly possible to ensure the happiness and quality of life of his bride. The Samoan historical record is full of instances when mistreatment of a wife was cause for serious consequence. When Vaetoeifaga (mother of Salamāsina) was insulted by her husband’s prior wives, Tui A’ana Tamaalelagi was blamed for not protecting his wife from cruelty, and the misdeed not only resulted in divorce, but also prompted a proportionally fierce military reaction from Vaetoeifaga’s family. When Fe’epō’s daughter Sina became disenchanted with her husband Tui Manu’a Fa’ato’ali’a, he escorted her back to ‘Upolu with a personal apology, and a fleet of ‘alia laden with apology gifts, including the famous Fale’ula house thatched with sega feathers. The imposition of Christian norms of authoritarian patriarchy and “the man rules his castle” mentalities were a major adjustment for Samoan families; Christian prohibitions on divorce and obligations to stay in adverse relationships “for better or worse” were diametrically opposed to pre-colonial norms that protected Samoan women from abusive situations and incentivized mutual power dynamics within marriage.

5. Several professional tautai specialties were known in former times included tautai folau (astronomers who navigated sea voyages), tautai faiva (expert fishermen who led expeditions), tautai o le ua (meteorologists who forecasted weather), tautai o matagi (topographers who selected sites and alignment of construction projects), tautai o le fue (honorific designation of master orators and tradition-keepers who mentored apprentices), etc.

6. The original Samoan word, more recently replaced with mālie due to tapuigoa practice.

7. In Si’umu, where Tu’u’u is a chiefly title, this fish is called palepō. One Faleata oral tradition links the story of the tuiga with the name avoidance practiced in Si’umu, since the tu’u’u was Vi’s favorite fish, and because Lele wore his headdress (pale) to court Vi at nighttime (pō), but I have not been able to corroborate this with any known account from Si’umu.

8. In olden times, the crown of the head (and the hair attached to it) was seen as a receptacle of mana power, vitality, and life force, and avoidance was strictly practiced. Cutting another’s hair without consent was an ultimate insult. Children were allowed to touch each other’s heads (as in childhood games like ‘e te lulu ‘e te moa and pōpō mano’o), but touching the crown of an adult head was strictly forbidden outside of close family relations.

9. The marriage of two people who were equally matched in both looks and temperament was praised as alofamāsaga (literally, “twin love”) and alofafe’oe’oea’i (“mutual/reciprocal love”). Had, Lele’s plan succeeded, his marriage with Vi would have been described as alofa uliulitauloto, referring to a surprisingly “unmatched” marriage between a young/gorgeous spouse and an old/unattractive partner.

10. One storyteller used words like tuigālama (stringing together candlenuts to make lamps/torches), tuigāi’a (tying fish together on a line), and tuigā’ato (arranging baskets to be carried on a shoulder pole) as linguistic support.

11. Lele was well-versed in plying mother-of-pearl and turtle shell, as these were the standard components of the pā fishing lures that comprised the bulk of the fisherman’s tacklebox

12. Oral tradition suggests that the precursor to the tuiga fau evolved from the carved, wooden selu tuiga combs which were inserted upright into the hair. Over time these combs increased in size and became more ornate, and accompanying adornments were added, such as the long tail feathers of the tropicbird (tava’e ‘ula), bundled tufts of dyed human hair, and painstakingly tied strands of sega feathers. Tuiga made in the post-contact era began to substitute mirrors, sequins and plastic gems instead of tifa and fuiono, and large chicken feathers have replaced the tiny sega plumage. There still exists linguistic evidence of more than one stylistic type of tuiga, which may have been attributable to regional preferences or perhaps artistic license). These terms include tuiga tavaʻe (tropicbird feather ornaments), tuiga ʻula (sega feather strands), tuiga lauulu (hair bundles), and tuiga vao (floral ornaments).

13. The word palefuiono is frequently misused today to refer to any ornamented headband, but in reality the term is reserved exclusively for the unique nautilus shell headband. Nowhere else in Polynesia, and perhaps Oceania, is there an analogous regalia fashioned from the pearlized nautilus shell, even in neighboring Tonga and Fiji, where countless other material culture traits are shared. The unsurpassed value of the fuiono (now largely forgotten), lay in its extreme rarity. The natural range of the nautilus is more than 300 meters below the ocean surface, and the only places where nautilus can be reached within depths accessible to human divers are the Solomons, New Caledonia, and Vanuatu (P.D. Ward, 1987, “Natural History of Nautilus”). In ancient times, an extraordinary international, multilingual, transoceanic social network transferred precious nautilus shells over 3,000 miles from the vicinity of Papua all the way to Sāmoa, increasing in value and scarcity at every leg of the long journey. While their market value (in modern terms) is impossible to assess, by the time these shells reached the skilled Samoan artisans who would incorporated them into palefuiono, they were arguably the rarest and most expensive of all Samoan commodities (even rarer and harder to acquire than exorbitant red sega feathers and treasured lei whale ivory).

14. Honorific word for hair. The process of tying small bundles of hair for use in tuiga is called fa’atavaitui.