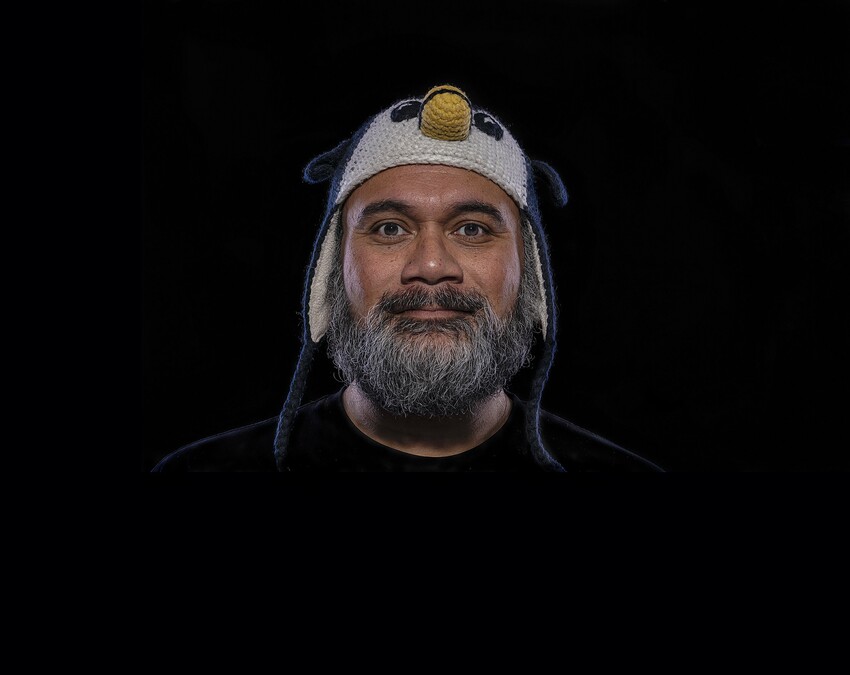

HUMANS OF THE ISLANDS - RAYMOND SAGAPOLUTELE

RAYMOND SAGAPOLUTELE

Photographer/ Visual Artist

Samoan

.

Tell us a bit about yourself - where were you born and raised?

Talofa lava and thanks for the opportunity to share. I was born at Middlemore Hospital in Otahuhu and I spent my early years in Invercargill and the Waikato and our family came back to South Auckland in 1980 and I’ve been a proud son of Manurewa ever since.

.

How did you first get into photography? Where did you make your start?

Mum and dad always had a camera in the house, they weren’t anything fancy and it was either a polaroid or those weird think Kodak cameras that used 110 film – they looked like those skinny little cameras you’d seen in spy films. I used to play around with them and some of my early photos are both awesome and hilarious. I didn’t take it seriously as part of my practice as an artist until around 2003 when, at my wife's insistence I took a couple of night classes to learn how to shoot, develop film and print. Since then, the camera became another way for me to frame stories.

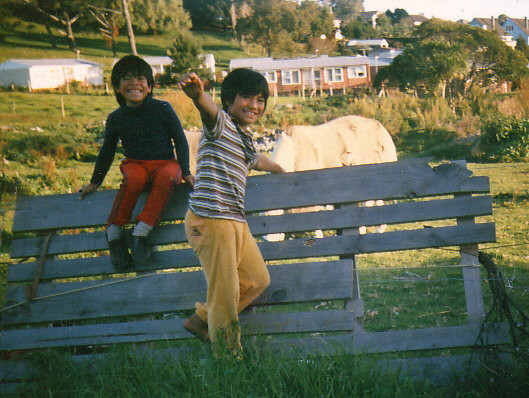

A photo Raymond took of his brothers Uoka and Mark back in the day

Some of your famous works like Siva Samoa and Poly Swag can provide a documentary of the progression of arts in Samoan culture. What inspires your photography works?

I don’t know if I’d call them famous, they were the images that made me go beyond just shooting what I saw and consider what it was I wanted to say. Taking photos of my family would be a given as I took my camera everywhere so social occasions were always a chance to catch time at that point with no narrative other than the occasion. I touched on the more personal aspect of my practice in the earlier days when I started shooting nocturnal landscapes around South Auckland. Those mages were about the land I was connected to during the hours I felt most open to seeing it – even if that was 2 am in the morning.

The Road Home

With the Siva images, my original intention was to shoot something comparative as my mum and my sister were both dancers but their styles were differentiated by culture and time. Mum based firmly in Fa’aSamoa (the Samoan way) and Tia representing contemporary hip-hop. Over time they have come to represent so much more to me, they are reminders of our peoples' resilience and determination to be who we are and at the same time, they remind me of everything I have lost. Several things are also tied to these that make them much more personal, this was the first and last time I shot my mum dancing, she passed away three months after shooting these. Tia has gone full circle with the evolution of her dance practice and come back to what mum had taught her when she was younger and researching and developing contemporary Siva Samoa is part of her practice. I learned through the process that photography is another tool in a long history of oratory among our cultures and its values lie not in the print but the story of those framed by the image.

Raymond's Mother - Siva Samoa

A lot of your photography documents natural human life/ the human condition, for example, your works "out of context", and Fatu Valu which comment on the multiple layers of Samoan life in a New Zealand context/ in general. What do you think it is about documentary/ portraiture photography that creates such meaningful images?

I think as per my previous answer the truth lies in the relationship the photographer has to the narrative they find themselves situated in. When I shoot people or events I don’t want to be seen. I don’t want to style my shoots so that people say – oh that’s Raymond – I would rather that when people look at the image they connect with the people or the event they are looking at. Out of Context, my ongoing project of the last five years haha, taught me quickly that it was never ‘my’ project to begin with. I have a duty of care to capture my sitters as they see themselves, I am just there to push the button. The end of Out of Context will be an exchange of time and space that specifically represents them in the 20-30mins they offered me.

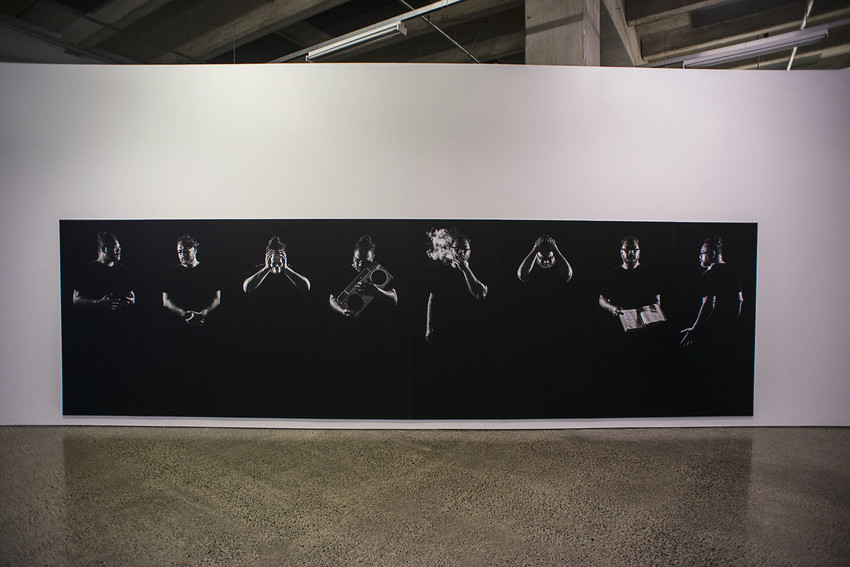

Out of Context

Fatuvalu was the culmination of my master's research and a pretty deep dive into my lived history and the connective relationships I have with my parents and siblings. It was at the time the summation of what I had to come to understand as a shared Samoan/Aotearoan history, one that didn’t just span my family's experiences. It intertwined with the experiences of many of those of us born as part of the diaspora in Aotearoa, raised in a dominant and different culture, far away from the lands our parents called home. The work is both documentary and lesson based on me – the term I used at the start of the process was ‘autoethnography’, work based on personal/lived experiences. I changed it to match the lesson received and rephrased to ‘fagogo’ – the old practice in Samoa of teaching via a narrator through performance, song, and chant. This taught me the value of retaining agency in the development of work tied to my heritage as a Samoan. It also made me more aware of the camera and the practice of photography as a means to continue our oratory practices via its purpose as a means to support the narrative as opposed to being the focus.

Fatuvalu installation

Have you always known you wanted to be a photographer? What is it about photography as an art form that drew you to it?

I originally wanted to be an astronaut as a kid, that or a pilot. I gave those ideas away as I got older and art was how I found a new way to fly. I have always enjoyed the freedom art gave me and any medium was awesome as long as I got a chance to create something. Photography became part of that creative need to express pretty late into my artistic journey, I was thirty-two when I picked up the camera. There’s an instant satisfaction that comes from photography now, the digital age has made it so much quicker to see what you’re doing. When I started, even as a kid using mum's camera, you had to wait and see what it was you got. That can be both a blessing and a curse and today its also very expensive as I no longer have a dark room. I like that I can paint with light, chase time and hold memories using this tool that even with all of its advancements still needs the eye of the artist to create.

Heritage Arts Fono

How do you think being a Polynesian/ Pacific person has impacted on your work?

When I was shooting editorial work for Rip It Up magazine and documenting concerts it usually meant I was often confused for security. In all seriousness though I don’t think there has been an impact if anything the influence of being part of our Moana community has always been there. I hadn’t taken notice of it until I chose to dive deeper into narratives and relationships connected to our family history and the wider Samoan community – a never-ending and hugely rewarding process.

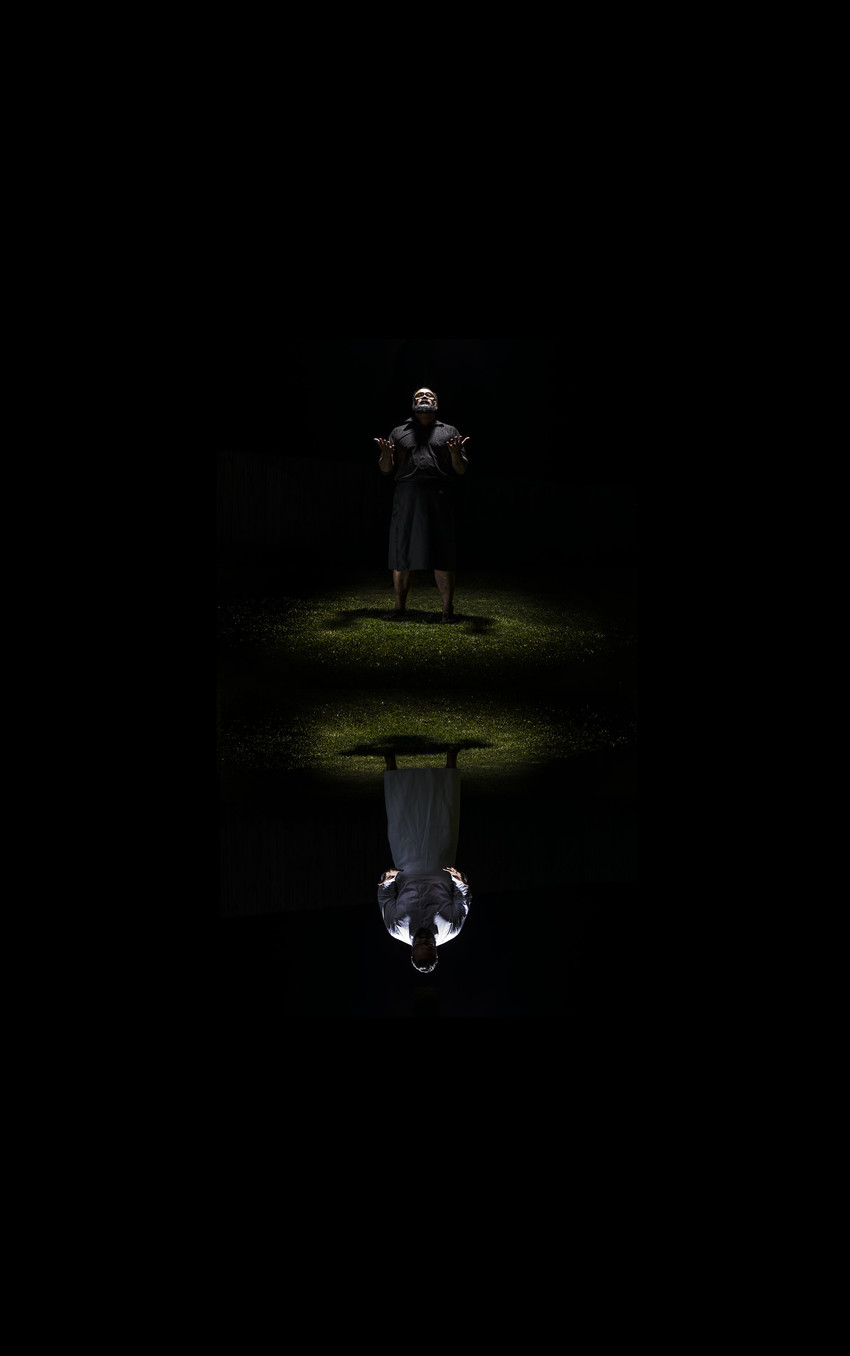

What artworks can we expect to see at the Auckland Festival of Photography?

I’ve approached the commission for the Festival from a different angle with the two images created. Based on my ‘Memento Moni’ series, work that looked at how in many Pacific cultures the head is sacred and how this was connected to narratives around my parents. I took this and applied it to the festival theme of ‘UNSEEN’ and used it as a platform to raise awareness of the struggle of the indigenous people of West Papua against what some see as the occupying presence of Indonesia. Looking to our aiga in the west of the Pacific has become important, too often we look towards the East but we have a connection and duty of care to the West of our Moana as well.

Momento Moni Series

Why are Festivals such as the AFP important to you?

AFoP is a great platform to share work, refine projects and network with local and international photographers. It’s a great way to support and promote studios and galleries that support our communities and over the years I have found AFoP and the team that organize and administers it a huge support with my journey as an artist. In 2016 they gave me my first taste of international exposure by including me in a group show curated by Rosanna Raymond. That experience connected me to so many people and opened my eyes to the global reality of shared experiences. Many of the people I met I consider close friends and part of my family.

Ray with Rosanna Raymond. PC - Linda T December

What was a major challenge you faced in your journey to becoming who you are today?

Self-doubt and imposter syndrome. In the past, I have found it hard to step in front of the camera and even harder to contextualise what it is I do without feeling like I’m wasting people's time. I have got a bit better at it but it’s never easy. So having that as a hurdle more often than not would make it harder for me to want to exhibit my work but with support from my wife, family and a huge network of incredible artists and friends it has been easier.

What do you see as your greatest success in your photography career?

I am always building, learning and changing as I create so any success I have is relative to the work I am making. If I am happy with it then that’s a success for me – happy usually means that somewhere along the line the work has frustrated me, made me crazy and with the images I deep dive into it also means a lot of crying. Not afraid to admit that. If I was to claim success it wouldn’t be around the work itself but more the ability of the art to allow me to have open and honest conversations.

Club Paradiso

What do you love the most about being a Pacific/ Polynesian photographer?

I love that I get to take something like a camera, and use it to tell our stories. At this point, most of the stories I tell with it are based around my lived experiences but that still connects back to the wider narrative of who we are. My work is not there to define what it is to be Samoan, Samoan in the diaspora, Polynesian or the wider Moana community. It’s just part of that larger tapestry that’s continually being woven and added to by all of our people.

One of the most valuable lessons I have learned is the importance of understanding. Understanding by connection to my elders and being respectful of the lessons they pass on because I can’t do what I do without knowing the background of my parents, my parents' parents and so on. The process I use and the stories I tell have a gafa, a genealogy and I must respect that when I am making. I can change and alter as a contemporary artist but if I do so just for the sake of change without understanding the background or my past I run the risk of breaking tapu. I learned this through talanoa with my elders and that’s something I never saw when I was framing things via a Palagi education. That I guess is part of the blessing of being a Moana creative. I may have wandered off a bit on the answer there.

If you have any advice for young pacific people who want to become a photographer, what advice would you give to them?

Learn the basics of photography and then break every rule if you want to. A camera is just a tool as much as a paintbrush is to a painter, you are the artist and it’s what you see or what you want to say that’s the real heart and soul of your work. One other pointer I would say would be to shoot, shoot and keep on shooting.

.

Raymond is exhibiting at the Auckland Festival of Photography which opens on the 27th of May and is on until the 14th of June. Click here for more details on the exhibition.

Check out more of his photography on his website RaymondSagapolutele.com

The Only Time