Lei Tei Dalo Ko Tamaqu - A Lullaby Of Loss

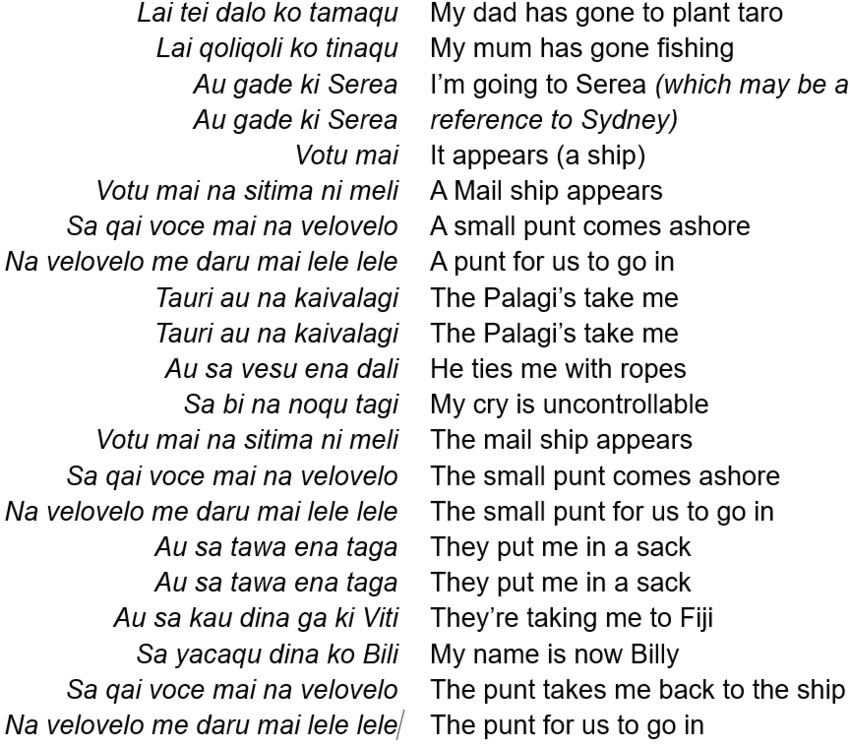

I remember a famous Fijian folk song titled “Lei Tei Dalo Ko Tamaqu” that we would sing to distressed babies or use as a lullaby to put our kids to sleep.

Knowing little of the dark history the musical notes entailed, it was tune that most Fijian kids sang their heart out too. Like how storytelling, music and dance was a form of relaying our history to younger generations, this folk song carried the weight, tears and heartbreak of our ancestors.

A simple song, but broken down opens a new chapter of clarity.

The sad reality of this folk song describes the inhumane capture of our Pacific Islanders, leaving behind their island homes for a life of turmoil on new land.

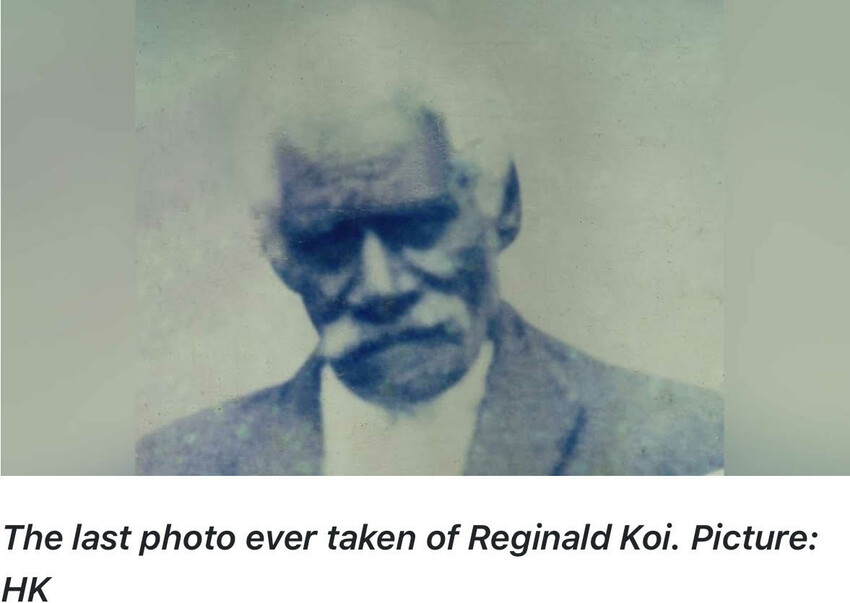

Evelyn Koi, descendant of Reginald Koi who was brought to Fiji from The Solomon Islands in 1883 through Blackbirding, describes learning about Blackbirding in school without the knowledge that she was a descendant of one of those caught in the captivity.

“I had no idea that I was a descendant until one day I read an article my uncle had written about the origins of the Koi family and how we stemmed from this inhumane capture”

Blackbirding, which took place primarily in the 19th and early 20th centuries, saw numerous South Pacific Islanders, collectively known as Kanakas, forcibly removed from their islands to work on cotton and sugar plantations in Australia, Fiji, and Samoa.

As these individuals left their homes, they carried with them the culture, stories, and traditions of their ancestors, which have since become a vital part of their descendants' identities.

Fiji now has suburbs dedicated to those who were brought over for work, in parts of Newtown, Tamavua-i-Wai, Valelevu and many more.

Mesu, also a descendant of the clan from Fataleka in the Malaita province, mentions how his family have settled in Fiji and have taken land in Wailoku forming the 5 villages (Vataleka, Malaita, Marata, Koyo and Bali) but staying true to their Solomon roots by naming them after the language of their forefathers.

When asked if given the opportunity to change what has happened would they change the tides?

“Those were dark times and things happen for a reason. We can only imagine the pain and suffering our ancestors went through but we have evolved and we continue to evolve. We now have our own little village in Newtown with the head of the Buka Clan being my granduncle”

Ms Koi adds “All that matters now is that we continue to pass on these stories to our children so they know who they are and where they come from - make them feel proud to be descendants of great people that contributed a whole lot to the development of Fiji”

“As a Christian, I can’t challenge what God has chosen for his people. But if that didn’t happen, I don’t think my people would have the same opportunities we have here than back in Bougainvillea. I am grateful for the sacrifices that my ancestors have made”

As we navigate the complexities of history, it is crucial to acknowledge the darker aspects that have shaped our present. The narrative of “Lei Tei Dalo Ko Tamaqu” serves not just as a lullaby but as a reminder of the resilience of the human spirit. It encapsulates the journey of those who endured unimaginable hardships and highlights the importance of remembering their sacrifices.

Through songs, stories, and cultural practices, the legacy of our ancestors can endure. As we engage with these histories, we foster a deeper understanding of our identities and the collective experiences that unite us. The echoes of the past remind us that while we may have come from places of pain, we have the power to create a legacy of strength and pride for generations to come.

-

By Jane Vavaitamana