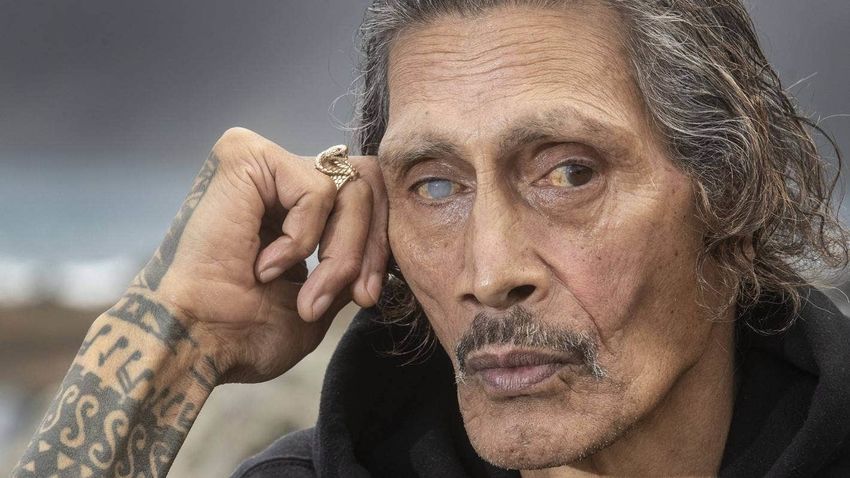

Abuse in NZ State Care - The Witness Testimony of Fa'amoana Luafutu

"I always considered myself to be like a taro shoot trying to grow in the snow — it can never happen you know...

When the State intervened and took me away from my parents, they became responsible for what happened to me in care and the pathway my life took into the borstals and prisons. We were put into a system that couldn't cater for us Pacific kids. The State shouldn't take you away if your life is going to be worse off. My parents had to pay maintenance for me when I was in care. We were already poor and struggling. I don't know how this would have made my parents feel. My parents shouldn't have been required to pay one cent to the State for looking after me."

The Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care is currently holding its first ever Pacific Investigation hearing into abuse in care of Pacific people in this country. The enquiry will look at abuse of Pacific people in both state and faith-based institutions between 1950 and 1999.

The name of this enquiry is Tulou - Our Pacific Voices: Tatala e Pulonga', at the Fale o Samoain Māngere and is open to the public from today through to the 30th July 2021. The scope of the hearing can be read here.

Fa'amoana Luafutu shares his witness statement below -

-

INTRODUCTION

My full name is Fa'amoana Luafutu. I was born in 1952 in Samoa and came to New Zealand at the age of 8 years old. Within 2 years I was before the Children's Board and in State care soon after.

I experienced all forms of abuse at Owairaka Boys' Home. I experienced physical abuse at other placements but for me Owairaka was the place that changed my life. By the time I left Owairaka the gun was already loaded, and the dye had been cast because of what happened to me there.

I am a playwright, author and musician. My story and the experiences of my abuse have been shared through the creative arts, for example in the plays 'The White Guitar' and 'A Boy Called Piano', as well as through my music and other writings.

By coming forward, speaking, and telling my story to the Inquiry, I hope there will be improvements in how the Government supports our Pacific migrant families and takes care of our kids who are in care.

EARLY LIFE IN NEW ZEALAND

When I came from Samoa, I could not speak a word of English. That made schooling really hard for my siblings and me.

We weren't allowed to speak English at home. Our parents said, "We brought you to New Zealand to be educated. We're not here to be educated so when you come home, you come back to your home language."

On my first day of school, I was given the name 'John'. The teachers said Fa'amoana couldn't be my name, they couldn't say it. They changed my name to make it easier for them. 'John' is what they called me from then on. This is how I came to be known as 'John Luafutu' throughout school and it carried on to my time in State care, prison and life after that.

Fa'amoana was my grandfather's name, it's a beautiful name. Part of my identity was erased when they gave me a new name. It marked the turning point of dislocation, dispossession, disorientation, disillusion and lost self-esteem experienced by me as a small child.

Back then there was no government support for migrant families who could not speak English,yet I was expected to go to school. Obviously,my schooling was going to be affected and I struggled to learn.

I vividly remember one time when the teacher told the class to do some homework. I went home and asked my aunty what homework was. She told me it was chores around the house (housework). So, I picked up rubbish and mowed the lawns a bit. The next day at school everyone got asked what they did for homework, and I said I cut the grass and picked up the rubbish. Everyone in the class laughed at me including the teacher. I didn't want to go back to school after that.

-

THE GANG

Auckland in the late 50s and 60s was a pretty racist place. This is why gangs were formed. The first Pacific Island gang, the King Cobras, was started in Ponsonby/Grey Lynn to protect immigrants from the racism that was going on and fight back against how our people were being treated, to support each other and form a brotherhood.

The King Cobras started with a Fijian Indian, Samoan and a Tongan. When thinking of a name for the gang, each person spoke about the most dangerous animal from their homeland. Our Fijian Indian mate explained that the most vicious snake in India was the King Cobra. The gang was named and the rest is history. I've been in the gangs for most of my life now and am a King Cobra Elder.

Following the King Cobras, other gangs were formed by brown people. Over time they started fighting against each other for turf and territory. One day, a leader brought everyone together and told them to stop the rivalry. A unified Black Panthers gang was formed. Members of the Black Panthers went on to form the Polynesian Panthers Party, a movement with a focus on socio-political matters.

The gangs gave us a sense of belonging in a country where we didn't feel we belonged. The gangs were there for me—before, during and after State care.

-

CIRCUMSTANCES LEADING INTO CARE

I wasn't behaving myself at school. I couldn't understand English or what was going on. My cousins and I, and other people like me, we just started playing truant and didn't go to school. That's how we first came to the attention of the State. It was deemed that we were out of control.

Not long after it felt like this group of ours were all being tarred with the same 'trouble' brush. We got to thinking that if they were going to treat us like animals, we are gonna act like that. This was the kind of attitude that was starting to be bred in us.

I was about 10 years old when I was placed under supervision. This is when I first came into contact with the State. I was around 12 years old when I was first taken on warrant and spent periods in the boys' home.

I remember being at the court with my mum. It was at the bottom of Queen Street. That's where the Children's Board was back in those days.

My mum said to me that I needed to listen to the people that were going to be looking after me because I was going away.

I remember my mum crying and so was my aunty. There were two of us going away, me and my cousin. We were being sent away to Owairaka Boys' Home. I thought it was like an adventure in a funny kind of way. I wasn't doing good at school, so I was glad I didn't have to go back.

From the outset, Owairaka was like a really flash looking place. It had really well- kept grounds. When I first saw it as this freshie kid from the Islands, I had never seen anything like it and thought it would be pretty good. But when I got in there, man it was just a nightmare.

-

MY ABUSE - OWAIRAKA BOYS' HOME

Kingpin Culture

At Owairaka there was a kingpin culture. The older boys that had been in there a while would stand over you and bully you.

When I came into Owairaka, the older boys didn't like me because I was a `coconut'. Those older boys could be so cruel to other boys, especially the new arrivals who were called 'wonks'.

There was 'stomping', a welcome to the club kind of initiation. You just had to harden up and take it.

When I first arrived, one night they put their boots in a pillowcase and just smashed the shit out of me. But I couldn't say anything. You learned not to be a tell-tale, not to be a nark. I learned to survive these things and really harden myself.

Everyone would go around saying "I wonder who can beat who up" — that sort of talk was always going around. There were all these tough guys there, and I soon realised I had to be the tough guy because I wanted to have the say around there —otherwise you were somebody's bitch, or you were cleaning somebody's crap.

Physical Training (PT)

I remember one time an escape happened. A few boys from the digger (secure unit) escaped and we had to do PT all day until the guys were caught. They weren't caught until 3 days later. I still remember the names of the staff who took turns making us do PT during those 3 days. There was one Maori staff member, the rest were Palagi and he was just as bad as the others.

The staff would have turns drilling us. It was PT all day every day for 3 days straight. And some of the PT exercises I just couldn't do. And if you couldn't do it, you got beat with the big wooden bamboo cane. If you couldn't lift your legs or squat lower and hold it for a certain amount of time, you got whacked.

Every time there was an escape the whole Boys' Home was put through PT until the runaways were caught.

For general PT we were made to run around and around the field in the cold mornings in bare feet underneath the Blue Gum trees and the twigs would just hurt your feet.

Another time my mate and I got into trouble, and we were made to scrub the yard down with toothbrushes.

There are too many examples I could give of the harsh and abusive treatment of us kids, it was like mental and physical torture.

The Digger —Secure Unit

I played up one time and I got thrown down the digger. Getting thrown down the digger was the secure unit.

I think I was there for 21 days on one stint. This is where I first experienced what they called the number one diet. If you were in the digger, you got the number one diet.

The number one diet was a piece of bread and a bit of dripping in the morning with a glass of milk. At lunch time it was a bit of bread and milk. On the third day you got a full meal.

You had a little bucket in the room to go to the toilet. Every morning they would wake you up at 6:00am and tell you to go empty your bucket out.

Sunday Boxing

On Sunday afternoons the boys would be taken into the lounge, and you would sit around in a ring and the staff would tell you to pick a partner. You would be given boxing gloves, go into the middle of the ring and just smash the shit out of each other. The boxing did not stop until somebody got a bloody nose or couldn't fight anymore.

Sunday boxing was held in the middle of the lounge where they would show movies sometimes if it was raining on a Saturday night. You just had to pick a partner. We were bloody shit scared, but we still had to get up and do it, we had no choice.

It was mainly the Housemaster who ran the Sunday boxing. After a while I came to see the cruelty in that guy. If you were new and he could see that you could maybe put up a good fight, he would pick somebody out for you that could really fight, someone that had been at the Home for longer and he would put you up for a welcome bashing. That was his own little sick buzz.

We were told to do what the white guys say and at that time I just accepted it. This is the way it was, do as you're told, the white guys clever and all of that. And I remembered what my mum said, to do exactly what they tell you to do.

The Digger Incident

It was not long before I started to have doubts about Owairaka because some of the Palagi men were really touchy feely.

There was the garden guy, he would bring nudist pornography books for the boys to look at.

I was down the digger one day and I came out of the shower, and he was standing there holding the towel. He tried to feel me up and I swore at him. He then said, "I wasn't trying to do anything to you little black bugger. Come on, grab your bucket son." He came around to me again holding the towel out, but I knew what he was trying to do, and he was eyeing me up. He tried it again the next day. It happened for 2 days. He would touch me, and I would pull away. He would say things like, "You got a nice tight little black bum."

I don't want to talk about this in any more detail. He wasn't the only one who tried things on. I ended up acting out because these bad things were happening. It became my defence mechanism —to nut out so I would get left alone.

I just got so down, so depressed and I felt helpless. I attempted suicide and tried to do myself away. That guy came in and held me up and yelled out to this other guy and they both got me down. The other guy said, "You silly boy". We went to the medical block and there they asked me, "What's wrong with you?". I said "nothing". I stayed silent, I could not tell anyone what had happened to me or what I was afraid of.

After all the things that were happening and the way they were running the Home, I just wanted to end my life. I have rarely told that part of my story before because it is something I have really tried to bury.

After this incident, I got taken back to the cell. The guards notified the superintendent and they kept me down there for another day. And then after that I was put out into the garden permanently. No more schooling. But I was way past schooling by then.

I was totally lost. I never used to pee the bed, but I did after the digger incident. I started wetting the bed. All those who wet the bed had to get up early and stand at the front of the door with their linen so every one could see. It was humiliating. We then had to take the linen down to the laundry.

Abuse of Others

At Owairaka almost all the other boys suffered the same treatment as me, some worse. There were some really vulnerable boys that couldn't cope, and who really struggled in there and later in life.

Contact with Family

During my time at Owairaka I never got to go home. My Mum came to visit me whenever she could. My Dad didn't come to see me, he barely spoke to me and wanted nothing to do with me. He was so disappointed and ashamed.

-

KOHITERE BOY'S TRAINING CENTRE

They couldn't handle me anymore at Owairaka so they said they were sending me to Kohitere to fix me up. My cousin and I got sent there together. By the time I got to Kohitere I was just like 'okay bring it on already'. After Owairaka it was just rebel, rebel, rebel. I didn't give a shit.

I went into Kohitere when I was about 14 years old. You weren't allowed to smoke cigarettes at Kohitere until you were 15 years old, that's how I remember because I had to wait a while before I could freely smoke.

They had school at Kohitere but I was way past school by then, so I ended up being sent to work in the forest, up in the Tararua Ranges. We were only young, and it was hard as work. But us boys liked being away from the Home, and they gave us time to be up there running around and yahooing. We would go back to Kohitere at night.

The only thing I had to worry about at Kohitere was being around these wannabe cowboys. There was a hierarchy there, and if you were a coconut you had to watch your back and have a backstop. This was somebody who would jump in if someone tried something on. You had to bring your back stop around with you.

By that time, I was able to defend myself. I formed the mantra —'When in doubt, nut out' —and if I ever felt that I needed to protect myself that's what I would do. But that all had consequences, being punished over and over again for bad behaviour, it was just a cycle.

I think I was one of the first to go in the Kohitere secure unit. I was there for 3 months. They had ex-army guys there, they used to train us. We had to do double time around the wing and they would shave our heads. It was like a detention centre the way they treated us. Smashing concrete foundations all day with sledge hammers was our job and you weren't allowed to talk to each other.

I was in Kohitere for about 20 months but it felt like years. I have mixed feelings when I think back to Kohitere. I made some good friends which carried on outside Kohitere. Most of the guys I met there I was to meet again, in borstals and prisons later on. I got into guitar playing and sports. But I also got to know a whole lot of negative things. I was confused and didn't know myself. The place had no function to meet the needs of a Samoan like me.

Just before I got out of Kohitere, I was allowed to go home for a week's leave.

Other than that, there were no regular visits but my family did write to me and send me cards sometimes. They could not afford to come and visit me when I was in Kohitere and far away places like that.

I don't remember a social worker coming to visit me and I don't remember having a lawyer representing me as a child.

I ended up running away from Kohitere, I just took off. I couldn't be stuffed with that place after a while. And then just thought fuck it, I'm out of here.

I got out of Kohitere in 1967. I remember because that's the year the decimal currency changed. I was 15 years old.

OTHER PLACEMENTS

Apart from Owairaka and Kohitere I went to many other placements. One placement that stands out for me was at a place in Ponsonby. They called it a youth hostel but really it was like a foster home. I was there with several other foster kids. I remember that I would have been 3rd form, but I wasn't going to school. I stayed at home.

The girls in that Home were getting sexually abused by the housemaster there. His wife would go to work, and he would take girls in the room and sexually abuse them. We were helpless. We couldn't do anything, and we couldn't say anything.

IMPACTS OF THE ABUSE

Later in life, I wrote a book called, 'A Boy Called Broke: My story, so far'. I would like to share an excerpt from 'Part B —Journey to the cells':

"Sometimes I'd be angry at God or whoever it was that made this world.

I had no idea of what I was gonna do once I got out.

Of the time I spent here the only good thing I learned was how to plant trees and scrub cutting,

but I did learn everything negative like burglary, shoplifting, drinking booze, home-brewing, armed robbery, safe cracking, tattooing andr ebel, rebel, rebel.

And a hatred for authority, arising from house masters in Owairaka, going on to screws in prisons.

When I think of Satalo and Poutasi and Falealili (the villages where I was born) and my present situation I realise sadly that I'll never be the same again.

Somewhere between Fa'amoana and John there was a breakdown (Gau) of sorts which had a devastating effect,

leaving me here staring at the concrete ceiling of my cell."

When the State intervened and took me away from my parents, they became responsible for what happened to me in care and the pathway my life took into the borstals and prisons. We were put into a system that couldn't cater for us Pacific kids. The State shouldn't take you away if your life is going to be worse off.

My parents had to pay maintenance for me when I was in care. We were already poor and struggling. I don't know how this would have made my parents feel. My parents shouldn't have been required to pay one cent to the State for looking after me.

After Owairaka I was changed. By the time I got to Kohitere, that anger was already built. I just didn't understand it.

So, by way of surviving, I nursed this deep anger within me, and I just ended up with this really vicious temper. And my wife can vouch for that I'm sorry to say, as can many others who crossed the wrong side of my path in life.

I think I managed to survive because I nursed anger like a baby. I had nowhere else to put those feelings and became a violent person. After the homes I just went in and out of prison and lived a life of crime.

In the jails where I ended up as an adult, I ended up running the jail. Because you have to be at the top to survive. When you entered the jail world you had to try and be at the top, be the kingpin, then you know you are successful and you are gonna be alright.

Like the homes, there is a hierarchy in jail. And if you make yourself vicious enough, the other vicious dogs will leave you alone. That's how it was. For example, we ended up attacking a prison warden just so that the other inmates would know you're not to be fucked around with.

THEATRE, MUSIC AND THE CREATIVE ARTS

In prison they didn't trust me outside with the other inmates. I was just beating everyone up. I lost all my privileges. So, they put me in the library, it was a safe place to keep me.

I found this book by Albert Wendt —'Sons for the Return Home'. When reading that book, I suddenly remembered a dream I had of my mum and my dad and why they came to New Zealand in the first place — for a better life. And that just blew me away. And I decided to change then.

I spoke to a psychotherapist and Father and let them into my heart. I told them what had happened to me. It saved me. Until I hit recovery, I didn't know why I had turned out the way I had. And all those people, they actually took me right back to the beginning of it all. And that's when I started to understand and get a clearer picture.

So, when I got out of prison in 1983, I thought I finally better go and do rehab. It took recovery and all that rehab stuff to be able look back on myself and understand. I have never been back to prison.

I came to realise that I had artistic and creative skills. Part of this journey was taking myself back to that little child I was and writing out my story from the beginning.

I am now a self-taught musician and an author. I also worked with my son on the film 'Ghost in the Shell' starring Scarlett Johansson.

I teamed up with a theatre production company called 'The Conch'. We did a play called 'The White Guitar', a true story about my family. My sons and I took part in the play. We touched on abuse in the boys' homes. 'The Conch' helped me articulate that story. We have since done another play 'A Boy Called Piano'. This play was written by me and performed by myself, my son and my grandsons. My hope is that the sharing of my story through the creative arts will help young Pacific people in their own journeys.

There were a whole lot of CYFS kids that came to see 'The White Guitar' and afterwards they all cried. I want these kids to know they're not by themselves, there are other people who have been through this abuse, who went through tough times growing up and understand what they are going through. I want them to see how they can use different mediums to express themselves.

Some of the kids were really enlightened. And that's what I am about. To initiate better change for the care of kids. To initiate change so they don't end up wasting their lives like I did.

Theatre, music and the creative arts gave me an outlet to express myself. The power of drama is massive and it can create social change. This is invaluable for children going through any care system. The State needs to foster the skills and talent of our children who would benefit from being able to express themselves in this way.

REDRESS

Accurate Records

I obtained my file from the State. My records show that in the Police Youth Aid reports I am recorded as non-Maori. There were two options to choose from: Maori or Non-Maori. I am Samoan, not non-Maori. It's important that our ethnicity, our identity, is recorded specifically and accurately.

Character

The people who work with our children should be good people who take a genuine interest and try to understand what has been going on for the child.

When my family first arrived, we needed support to adapt to the New Zealand way of life, not judgment and an expectation that we just fit in straight away. My parents' dream of a better life collided with the cultural ignorance of mainstream New Zealand in the 1950s onwards.

A number of my welfare case notes show the derogatory views held towards Pacific Island migrants. Some comments such as:

"This 10 year old boy comes from a family which has failed to appreciate New Zealand ways and a lack of understanding of the English language."

"Here again, this is an Island boy having language troubles. Neither Mr or Mrs Luafutu speak very much English."

"This 12 year old boy comes from a family who have not settled into European ways readily and cling to a Samoan language and dress. If the parents would take a greater interest in English, then they would have been able to assist their boy to a far greater extent."

"This family clings to its Samoan language and customs and though they have been in New Zealand for some years they have not made the effort to accustom themselves to European ways..."

Migration is still happening now. If me sharing my story results in this country looking at ways to receive our migrants properly and giving their kids better support, then it was worth it and that is part of redress for me.

My life's pretty much gone now, but I hope that what I have shared will make improvements for the future. The stuff with my Samoan language, going to school with no support, there was no help, no nothing. And I couldn't go home and say help me.

There was the State/ Children's Board, then they gave it another name CYFS. Now it's Oranga Tamariki. And it's ironic to me that mostly all brown people are in the jails now. I want to say to the Government, it's not about more youth homes and jails —we don't need to build more of these places, we just need to come up with better ideas on how to handle young people.

There was just no understanding about our behaviours or why kids might be playing up before going into care, why we were acting out or wetting the beds in the homes. No one asked us or spoke to us to see if it was a sign of distress or if something else was going on.

MSD Claim

In 2016, I lodged a claim with the MSD historical claims unit ("MSD").

I was interviewed in August 2017.

At the beginning of the recorded interview, I was asked to say my name. I responded "Fa'amoana Luafutu". The lady then said, "Ok John, and who have you brought with you today?". I had just stated that my name was Fa'amoana yet I was called John. Soon after I was asked, "What name would you like us to call you?". I responded, "I don't care, I don't care what you call me, whatever's easier."

I wasn't there for the money. No amount of money could ever come close to repaying what was taken away from me. After the interview ended, nothing happened for ages. I remember getting a letter making a rubbish offer and I signed the paper accepting it and sent it off.

I never had the chance to say how I felt when I was in the boys' homes. That is the reason why I spoke to MSD. I felt that the system needed me to say something because it was always them making reports about me, but they didn't know anything about me.

In speaking to MSD, I was hoping that after telling them my situation there would be a release of that baby I speak of so it can finally just die because I carry it with me all the time. Something snaps in my head, and I just go off, just fly off. Even though I've done recovery, if I'm drinking, it is just a little flick and then man I'll just turn just like that. And I didn't want to be like that anymore.

But I know that's from all the stuff that's happened to me as a kid, and it's affected my life as an adult. That was why I spoke to MSD and why I'm now speaking to the Inquiry —to let you know that the system that I was brought into failed me.

I encourage others who were abused in the homes, foster care and borstals to come forward and speak out. I saw a couple of guys who had been on TV talking about stuff that happened to them in State care and I was encouraged by that. I just thought good on you bro and it gave me the courage to speak out. I am hoping that other guys will do the same, especially our Pacific people. Our stories will be similar, the abuse we suffered as kids in the welfare homes. We were just innocent kids.

-

LATER LIFE

My sisters Losa and Lili, and cousins Atenai and Saia Saifiti, who have now all passed, went into care too for the same reasons I was placed there. My parents were just lost, it destroyed them. They were just as lost as me and my siblings. My siblings and I look back in sadness. Sometimes we have family dinners and think about Mum and Dad. Dad died at the age of 51. He tried to reverse the dream as it were, and he went back to Samoa to build a house. He was diagnosed with cancer. They brought him back to New Zealand and he died.

It is also sad because whilst I am able to do this, my cousin who went through the boys' homes with me from the beginning now has cancer and dementia. I go and see him when I can. He's still a tough guy but when I look at him now, I keep thinking of us as kids. I can't help but think back and wonder what happened to us but of course I know what happened to us.

This is why I say that I have always considered myself to be like a taro shoot trying to grow in the snow —it can never happen. Here I was, this young freshie Samoan taro boy from the Islands expected to grow and thrive in New Zealand. But without the right environment, the right support and nurturing, it was never going to happen.

I would sometimes go to Grey Lynn, just to stand and look at the house we lived in, just to relive memories of living in that house. I would do that to re-examine myself.

After making the claim with MSD, sharing my story through my writings, music, drama, the creative arts, and now speaking to the Inquiry, I hope that won't happen so much, now that I've talked and been able to let out what I've been holding inside for so long. There are some things that a psychotherapist can't help you with. I felt like it was the system that I needed to address so that is why

I engaged with MSD and have come forward to the Inquiry.

I still have that angry little baby inside but its asleep most of the time. And I try and keep it that way. But sharing my story helps me put that baby in a deeper sleep each time.

* Cover photo credit: Kevin Stent for Stuff